Friday, August 3, 2007

Idling: Who Cares?

During Q3, the third period of qualifying, the cars circulate the track at speed, trying to burn off as much fuel as possible. As we've discussed, an F1 car is generally faster in 'clean' air than running close behind another car. So what should you do? Since you get fuel credit for each lap you run, if you're really keen on your strategy you may be able to run 1-2 more laps than everyone else, thus burning off more fuel (making the car faster for the last lap of qualifying) and also gaining extra fuel to put back into the car to start the race.

So to get clean air and the maximum possible number of laps in, you want to have your car first onto the track when Q3 starts. So the teams start to line up at the pit exit line early, waiting for the green light. Only one problem with this; F1 cars don't like to sit still.

Normally a regular car's engine has no problem idling, afterall, its designed to. But an F1 engine generates a tremendous amount of power and subsequently heat. It also idles at around 4,000 rpm, much higher than the leisurely 800-900 rpms a street car turns. The car's radiators will easily cool the car, however F1 cars don't have fan's to pull air through the radiator. Fans aren't necessary if the car is moving, and they're a liable to break or imped airflow at speed so they're naturally left off an F1 car. Which brings up a real problem: how do we get our car first in line to get on track and not have it overheat while we wait?

Way back in 1981 Cadillac introduced a mouthful of an engine; the "V8-6-4 (L62)". The part that's important is the V8-6-4. This was the first engine with 'displacement-on-demand' or the ability to turn from a V8 into a V6 into a V4 all electronically. The engine normally worked as a V8 eight cylinder engine, but would deactivate varying cylinders when the engine wasn't working hard, like on the highway, to get better fuel mileage.

It didn't really work out that well and GM eventually withdrew the technology. My neighbor growing up had a car with one of these engines. I always remember it because it had a novel (for the time) talking car module. It would say things like "Door is ajar. Door is ajar." whenever a door was opened or "Fasten seat belts please." Quite annoying actually. Anyway, this guy had so much trouble with the engine that eventually the service center had a GM engineer come out with his suitcase-sized 'laptop' to diagnose the issue.

Later GM did get this technology to work, and they used it on the 'Premium V' engine initially as a failsafe mechanism to save the engine if all the coolant was drained. The coolant (aka 'anti-freeze') is the water/ethylene glycol mixture that circulates inside of the engine block, carrying heat away to the radiator, cooling, and running back into the block again. (The glycol keeps the water from freezing when its cold out). Without coolant, the engine overheats, causing all sorts of warping and general nastiness that quickly results in a useless lump. The point is: by cutting out varying cylinders and running the engine like a V4, the engine does not produce as much heat and can actually cool itself simply with air.

F1 engineers are a clever bunch and resurrected this trick for their own cause. So now you know. Those glorious V8 F1 engines are, at least for the few minutes they wait to exit pit-lane, really just 1.2L 4-cylinder engines.

Which brings up an interesting point. At the 2007 European Grand Prix, after a dry start, torrential rain covered the first corner by lap 3. Six (yes that's right, six world-class drivers) went off the track in turn 1, including one Lewis Hamilton. It was comical. Conditions were so bad that the remaining cars, on full-wet tires, couldn't even keep up with the safety car. The race was red flagged until the rain subsided. However of the cars off in turn 1, only Lewis Hamilton rejoined the race, although several others were undamaged. The reason? He was the only one who kept his engine running. The other cars either stalled or didn't have the software to allow the engine to idle for a long period while the cars were extracted by crane from the gravel-trap. But Hamilton immediately got on his radio asking his engineer what to do so he could engage the idle mode and save his race. Smart lad!

Friday, July 27, 2007

Introduction to the Racing Line or WTF is a 'chicane'?

To figure out where the line is and why, we must first understand what happens in a corner. In a race car, we strive to be using all of the car and its tires at all times. This means we are always accelerating at full throttle when possible, and we're always braking as hard as possible. As we've talked about, tires grip both longitudinally and laterally. These grip levels are not independent of each other; if you are using all of the tires' grip to brake, you won't be able to turn. This is very easy to try for yourself in an empty lot.

To figure out where the line is and why, we must first understand what happens in a corner. In a race car, we strive to be using all of the car and its tires at all times. This means we are always accelerating at full throttle when possible, and we're always braking as hard as possible. As we've talked about, tires grip both longitudinally and laterally. These grip levels are not independent of each other; if you are using all of the tires' grip to brake, you won't be able to turn. This is very easy to try for yourself in an empty lot.We can better visualize this idea of available grip with the 'traction circle'. The basic idea is that at any time the tire has 100% of its grip to be allocated to turning, braking, and accelerating. So you can turn and brake at the same time, but only in a combination that doesn't exceed 100%, say 60% braking/40% turning.

Let's pretend we are in our race car headed for a 90 degree left turn. We'll stay 100% on the throttle until we get to our 'braking point'. The braking point is some point before the corner when 100% braking should start. This point is far enough ahead of the corner that the car will slow down enough to make the corner.

Let's pretend we are in our race car headed for a 90 degree left turn. We'll stay 100% on the throttle until we get to our 'braking point'. The braking point is some point before the corner when 100% braking should start. This point is far enough ahead of the corner that the car will slow down enough to make the corner.Usually the best line through the corner is the one with the widest possible radius. This means that coming into the corner, we want to place the car on the right side of the track; outside for a left-hand turn. After we finish braking, we reach the 'turn-in' point, the point at which we begin to steer the car to the left. We'll aim the car at the left side of the track at the innermost point of the corner. This is the 'apex'. From the apex, we slowly unwind the steering wheel and begin to squeeze the accelerator. We aim the car at the right (outside) edge of the corner.

So the pattern for a simple corner is outside-inside-outside. The car lines up as far as possible away from the corner (outside), drives an arc that clips the apex (inside), and then tracks out to the edge of the track (outside).

So the pattern for a simple corner is outside-inside-outside. The car lines up as far as possible away from the corner (outside), drives an arc that clips the apex (inside), and then tracks out to the edge of the track (outside).Now things are not quite that simple. There are various positions of apexes, described as early or late. An early apex means turning the car and continuing to brake into the corner, than adding more steering at the apex. A late apex means keeping the car outside longer, then adding steering to get to the apex, then reducing steering and accelerating. Basically, an early apex is faster into the turn, a late apex is faster out of the turn. So which one is right? Well it depends on the track. If there is a long straight after the turn, a late apex will be faster. But if there is a long straight before the turn, and another turn immediately after, an early apex line may be faster. Generally speaking, the ideal line is a late apex line.

Here's another view of the various lines. The green line represents a 'neutral' apex line; the line that would be the fastest through the turn, ignoring the straight parts of the track before and after. The dark blue line represents the early apex line. You can see by pointing the car towards the apex, the early apex line begins with the car traveling straight towards the apex. During this time the early apex driver can brake, but the early apex line then must turn tighter after the apex to stay on track. The light blue line represents the late apex. With this line, the driver does all the braking before turning in. The late apex line has to do more turning before the apex, but then gets a straight shot to accelerate after the apex. Thus the common racing adage for late-apexing: "slow in, fast out".

Here's another view of the various lines. The green line represents a 'neutral' apex line; the line that would be the fastest through the turn, ignoring the straight parts of the track before and after. The dark blue line represents the early apex line. You can see by pointing the car towards the apex, the early apex line begins with the car traveling straight towards the apex. During this time the early apex driver can brake, but the early apex line then must turn tighter after the apex to stay on track. The light blue line represents the late apex. With this line, the driver does all the braking before turning in. The late apex line has to do more turning before the apex, but then gets a straight shot to accelerate after the apex. Thus the common racing adage for late-apexing: "slow in, fast out". Things get even more complicated when we consider a series of corners, not just one turn in isolation. Often there may be 3 or 4 turns strung together which requires a 'compromise' line; a line that may not be ideal in each turn, but overall results in the best speed.

Things get even more complicated when we consider a series of corners, not just one turn in isolation. Often there may be 3 or 4 turns strung together which requires a 'compromise' line; a line that may not be ideal in each turn, but overall results in the best speed. Racers have come up with some general terms to describe types of corners. First is the 'sweeper'; a long, flowing high-speed turn, similar to a long circular off-ramp. An 'S' or 'Esses' is a combination of alternating turns in an 'S' shape, as you might expect. A 'hairpin' is a turn that is usually about 180 degrees and quite slow, usually with a straight leading in and another leading out. Finally, a 'chicane' (pronounced "sha-kane") is a tight left-right or right-left combination, usually at the end or middle of a straight. Often, chicanes are added to tracks to slow the cars down. Often times a chicane will have cones or soft barriers marking the edges of the track to minimize risk to a driver who enters the turn too fast. If a driver does miss the chicane, they can drive back onto the track, but they cannot gain any positions. The Ferrari at right is entering a chicane. The two cones mark the apexes of the turns.

Racers have come up with some general terms to describe types of corners. First is the 'sweeper'; a long, flowing high-speed turn, similar to a long circular off-ramp. An 'S' or 'Esses' is a combination of alternating turns in an 'S' shape, as you might expect. A 'hairpin' is a turn that is usually about 180 degrees and quite slow, usually with a straight leading in and another leading out. Finally, a 'chicane' (pronounced "sha-kane") is a tight left-right or right-left combination, usually at the end or middle of a straight. Often, chicanes are added to tracks to slow the cars down. Often times a chicane will have cones or soft barriers marking the edges of the track to minimize risk to a driver who enters the turn too fast. If a driver does miss the chicane, they can drive back onto the track, but they cannot gain any positions. The Ferrari at right is entering a chicane. The two cones mark the apexes of the turns.Now maybe you can see why the drivers get paid so much. Finding the line and hitting it consistently lap after lap, with the car on its limits of grip is quite difficult, and even more-so in the pinnacle of cornering which is the F1 car.

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

The Car of Tomorrow: Part 1 - the chassis

Its no secret that the FIA's working group wants to increase overtaking, thereby increase the spectacle of the racing. However, there's a fundamental problem here. The FIA wants to ensure that F1 cars are the fastest around a road course; faster than any other racing series. To do this, the cars have to make downforce. But as we've talked about before, inherent in making downforce is leaving turbulent air behind the car, which greatly reduces the effectiveness of the wings on a car following in this wake.

Its no secret that the FIA's working group wants to increase overtaking, thereby increase the spectacle of the racing. However, there's a fundamental problem here. The FIA wants to ensure that F1 cars are the fastest around a road course; faster than any other racing series. To do this, the cars have to make downforce. But as we've talked about before, inherent in making downforce is leaving turbulent air behind the car, which greatly reduces the effectiveness of the wings on a car following in this wake. The FIA considered several ideas to try to address this issue, including a rather interesting design called the Centerline Downwash Generating (CDG) wing; basically a wing with the middle section cut out. The aim was that clean air would flow through the middle and downwards, given the trailing car's front wing good air to work with. However, Racecar Engineering (a magazine) did simulations that showed the CDG wing only made the situation more complicated and probably worse for the trailing car.

The FIA considered several ideas to try to address this issue, including a rather interesting design called the Centerline Downwash Generating (CDG) wing; basically a wing with the middle section cut out. The aim was that clean air would flow through the middle and downwards, given the trailing car's front wing good air to work with. However, Racecar Engineering (a magazine) did simulations that showed the CDG wing only made the situation more complicated and probably worse for the trailing car.Which brings us to the current proposed solutions: active aero. I've been a proponent of this idea for a long time, so I'm very excited to see what will happen. The basics are this: within a given range specified by the FIA, the teams will be able to electronically adjust the angle of their wings. The cars will also have a turbulence sensor fitted, and when turbulence is detected, the ride height of the car will be lowered. This puts the car closer to the track, increasing the downforce the car is able to generate. A leading car cannot lower its ride height below baseline. With active wings and active ride height, the FIA hopes to increase overtaking.

The rule changes are also taking into account the application of F1 technologies to road cars. One common area that both road and racing cars hope to reduce is drag. Obviously the need to create downforce creates drag, but downforce is not needed during straight-line driving. On a road car, there is no need to create large amounts of downforce, but the designers must prevent lift at high speed to prevent the car from becoming airborne. This is why many Porsche 911's had spoilers that automatically deployed at highway speeds.

The rule changes are also taking into account the application of F1 technologies to road cars. One common area that both road and racing cars hope to reduce is drag. Obviously the need to create downforce creates drag, but downforce is not needed during straight-line driving. On a road car, there is no need to create large amounts of downforce, but the designers must prevent lift at high speed to prevent the car from becoming airborne. This is why many Porsche 911's had spoilers that automatically deployed at highway speeds.Drag is also created by letting air flow into the car, namely for cooling purposes. Typically, a car (both racing and road) is developed with a radiator opening for largely the worst possible cooling case. However, when the car is traveling at speed, this opening doesn't need to be as large since there is more and flowing over the radiator. By reducing the opening, drag is reduced. This is practical on a road car to increase fuel mileage, and will be allowed in F1 for 2011.

There was talk that the front and rear wings would become spec items, however the FIA has decided that the wings are an important element of styling and the FIA does not wish to have a field of identical-looking cars. However, to control development costs the number of elements (essentially separate wings) in the wing will be limited. The floors of the cars will become spec, with a design that is said to lessen the effectiveness of the front wing.

There are also attempts to ban 'aero-plasticity'; basically a fancy word for wings/floors that bend or move at high speeds. Ferrari developed a rear wing with a slot in it, so that at low speeds the slot would be closed, but at high speeds the air would bend the wing, enlarging the slot and allowing more air through, reducing drag (and increasing top speed). There are also claims that McLaren's front wing and Ferrari's floor both flex at speed. Determining if a part flexes or not is quite difficult, as the FIA specifies a bending test, but this test is carried out in the garage and doesn't use nearly the force that high-speed air puts on a part. The FIA hopes that by allowing other aero technologies, teams won't have to resort to these kind of shenanigans.

There's also talk of some very new and very interesting aero technologies being allowed. Aerodynamics is a complicated topic, but one of the common issues is 'flow detachment'. Basically when air hits a surface, the air will flow along the surface until at some point (perhaps the end of the surface) it 'detaches'. This detachment leaves swirling vortices of air that cause drag. To overcome this, several new technologies are being considered.

There's also talk of some very new and very interesting aero technologies being allowed. Aerodynamics is a complicated topic, but one of the common issues is 'flow detachment'. Basically when air hits a surface, the air will flow along the surface until at some point (perhaps the end of the surface) it 'detaches'. This detachment leaves swirling vortices of air that cause drag. To overcome this, several new technologies are being considered.First is the plasma generator, which works by having an electric strip along the leading edge of the wing which ionizes (charges) the air. A second charged strip is placed farther back on the surface, which then attracts the charged air, preventing flow detachment. Another idea is MEMS; Micro-fabricated Electro-Mechanical Systems. Basically it’s a strip very tiny little vibrators on the leading edge that create turbulence in the 'boundary layer', which is the layer of air very close to the surface. This air essentially 'sticks' to the wing, but doesn't flow off, thereby increasing the effective thickness of the wing. Creating turbulence in this layer reduces its thickness, reducing drag and flow detachment. This can also be accomplished by tiny holes in the surface, which jet air into the boundary layer.

One problem in aerodynamics is that its difficult to scale things; meaning you can't use small models. Clearly it would be vastly easier and less expensive to build a 1:10 scale wind tunnel and use 1:10 scale models to test designs. However, it turns out that anything less than a 1:2 model doesn't relate well to the full-size car. Its also important to model the effect of the moving road. Therefore, teams have had to construct full-size wind tunnels with rolling roads to get good information. Obviously building and running these full-size tunnels is very expensive. One of the new techniques to model aero is CFD (computational fluid dynamics); basically a computer simulation. Only recently have computers become powerful enough to approximate the complex airflow seen by an F1 car. In fact, the Williams team just bought a supercomputer for this very purpose!

So the new rules argue that most of the teams already have the aero testing facilities, so the new aero rules won't cost significantly more to implement. In fact, there should be cost savings because the adjustability will allow for easier tuning of the car in all situations, instead of having to build 400 wings just to find the one that is the perfect fit for that week's circuit.

In the next installment we'll explore the powertrain regulations for 2011.

Saturday, July 14, 2007

Tires

You know what they say (or rather Goodyear said in its ad's in the 60's) "Where the rubber meets the road." And that is indeed one of the most critical interactions in F1. Tires have always played a huge roll in F1, and while some new rules have slightly diminished that importance, the talk in the paddock during practice is always about the tires and how to find more grip.

You know what they say (or rather Goodyear said in its ad's in the 60's) "Where the rubber meets the road." And that is indeed one of the most critical interactions in F1. Tires have always played a huge roll in F1, and while some new rules have slightly diminished that importance, the talk in the paddock during practice is always about the tires and how to find more grip. In the past, teams were free to run whatever brand of tires they wanted, provided the size of the tire meet basic requirements. The start of the modern 'tire war' in F1 was in 2001, when Michelin entered F1 to challenge the then monopoly of Bridgestone.

In the past, teams were free to run whatever brand of tires they wanted, provided the size of the tire meet basic requirements. The start of the modern 'tire war' in F1 was in 2001, when Michelin entered F1 to challenge the then monopoly of Bridgestone.In physics terms, all tires work basically the same. The idea is to create a tire that will have high friction in all directions. You need longitudinal grip (along the direction the tire rolls) for good acceleration and braking, and lateral grip (sideways) for cornering. Your typical street tire accomplishes this through mechanical friction. The more rubber that touches the road, the better as far as grip is concerned. So you may wonder why your street tires have various grooves and slots; the "tread pattern". The street tire is designed with the voids to channel away water (and snow and mud) from coming between the tread block (the part that touches the road) and the pavement, which helps to avoid hydroplaning. Hydroplaning happens when water builds up between the pavement and the tread block, leading to a loss of traction.

So it should be clear that a racing tire, designed for maximum dry, warm-weather conditions will be a 'slick' or have no voids (no tread pattern, like the blue car at right). And in most racing series, this is still the case. However, in F1 the speeds were getting too fast, so the FIA attempted to slow the cars down by mandating that the tires have several grooves molded into them, reducing the effective area of the tire (see far right).

So it should be clear that a racing tire, designed for maximum dry, warm-weather conditions will be a 'slick' or have no voids (no tread pattern, like the blue car at right). And in most racing series, this is still the case. However, in F1 the speeds were getting too fast, so the FIA attempted to slow the cars down by mandating that the tires have several grooves molded into them, reducing the effective area of the tire (see far right). We've talked before about the aero loads (downforce) that the cars achieve. Ideally, we'd want our wings attached directly to the wheel hubs or suspension, which would then push down only on the tire, and leave the body of the car free to move up and down to absorb bumps. However, due to some spectacular failures of suspension-mounted wings, these were quickly banned and now any aero surface must attach to the body of the car. This means that the downforce pushes the body down, which then compresses the suspension of the car. In order to keep the car from bottoming out, the teams must run a very stiff suspension, which has a travel of only a few inches.

We've talked before about the aero loads (downforce) that the cars achieve. Ideally, we'd want our wings attached directly to the wheel hubs or suspension, which would then push down only on the tire, and leave the body of the car free to move up and down to absorb bumps. However, due to some spectacular failures of suspension-mounted wings, these were quickly banned and now any aero surface must attach to the body of the car. This means that the downforce pushes the body down, which then compresses the suspension of the car. In order to keep the car from bottoming out, the teams must run a very stiff suspension, which has a travel of only a few inches. Ideally we'd like to have a softer suspension to deal with bumps on the track, but since that's not possible, teams turned to tires. You'll notice that the sidewall of the tire is quite tall in F1. Contrast this to the very short sidewalls on this LMP Porsche in the Le Mans series at right. This is because the tire actually is the majority of the suspension of the car! The tire is designed to deform to absorb bumps and maximize grip. This means that since the tire is also largely the suspension, understanding and having correct tires is critical in F1. Most teams partnered with a tire supplier and designed their cars around getting maximum use out of the tire.

Ideally we'd like to have a softer suspension to deal with bumps on the track, but since that's not possible, teams turned to tires. You'll notice that the sidewall of the tire is quite tall in F1. Contrast this to the very short sidewalls on this LMP Porsche in the Le Mans series at right. This is because the tire actually is the majority of the suspension of the car! The tire is designed to deform to absorb bumps and maximize grip. This means that since the tire is also largely the suspension, understanding and having correct tires is critical in F1. Most teams partnered with a tire supplier and designed their cars around getting maximum use out of the tire.During the tire war from 2001-2006, the tire engineers went nuts. They developed special compounds for each race of the season, sometimes multiple compounds for different air temperatures at the track. The tires are quite sensitive to heat, and need to be at the proper temperature to work. Too hot or too cold and the grip will be less than optimal, and the surface of the tire may start to degrade. You'll see whenever the cars change tires, the tires are wrapped in special blankets. These are tire warmers that heat up the tires to near track temperature, so when the driver goes back out, there's at least some heat in the tires.

During this period there were several changes in the tire regulations. For a while, the cars had to qualify and complete the race on a single set of tires. This rule was designed to make the teams run harder tires, which have less grip, and therefore slow the cars down. The result was actually more dangerous, as the drivers would still want to run as soft of tire as possible, even if it meant risking a failure, and eventually this lead to the US-GP debacle in 2005.

Now for 2007, the tire war is officially over, with Bridgestone becoming the sole supplier of tires. Bridgestone has developed five tire compounds that will be used for the entire season, and all teams get identical tires. These compounds range from super-soft to hard. For each track, Bridgestone selects two of these compounds. The harder of the two will be designated the 'prime' or 'hard' tire for that race, while the softer tire will be referred to as the 'option' or 'soft' for the race. This can be a little confusing in some cases, like Monaco, where Bridgestone brought their super-soft and soft tires, which were then called "soft" and "hard" respectively, for that particular race. The "prime" and "option" terminology is better, and its what most of the teams use.

Now for 2007, the tire war is officially over, with Bridgestone becoming the sole supplier of tires. Bridgestone has developed five tire compounds that will be used for the entire season, and all teams get identical tires. These compounds range from super-soft to hard. For each track, Bridgestone selects two of these compounds. The harder of the two will be designated the 'prime' or 'hard' tire for that race, while the softer tire will be referred to as the 'option' or 'soft' for the race. This can be a little confusing in some cases, like Monaco, where Bridgestone brought their super-soft and soft tires, which were then called "soft" and "hard" respectively, for that particular race. The "prime" and "option" terminology is better, and its what most of the teams use. The rules specifiy that during the race each car must use both types of tire at least once. The option tire is distinguished by a white stripe painted in one of the grooves on the tire. Most teams have said that the option tire tends to be a little faster, but doesn't last nearly as long. They tend to be good for one or two fast laps, and then begin to degrade. Most teams have found the prime tire to be more consistent over many laps.

The rules specifiy that during the race each car must use both types of tire at least once. The option tire is distinguished by a white stripe painted in one of the grooves on the tire. Most teams have said that the option tire tends to be a little faster, but doesn't last nearly as long. They tend to be good for one or two fast laps, and then begin to degrade. Most teams have found the prime tire to be more consistent over many laps. Unlike many other forms of motorsports, particularly those that compete on ovals, F1 races are not usually cancelled or stopped due to rain. Hence, Bridgestone also supplies 'intermediate' and 'wet' tires for non-dry conditions. (At right is a full wet tire).

Unlike many other forms of motorsports, particularly those that compete on ovals, F1 races are not usually cancelled or stopped due to rain. Hence, Bridgestone also supplies 'intermediate' and 'wet' tires for non-dry conditions. (At right is a full wet tire).

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Politics and Drama

The FIA, or Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile, started in 1904 as a sanctioning body for auto racing. They organized the first world championship, which evolved into what is now Formula 1. They make the rules governing the construction of the cars, and they enforce the racing rules when cars are on-track. Typically major decisions are handled by the FIA president, who since 1991 has been Max Mosley. Pay attention, because you'll see his name pop up a lot in F1-land. Before Max, the president was Jean-Marie Balestre (facing the camera at right), who enters into play next.

The FIA, or Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile, started in 1904 as a sanctioning body for auto racing. They organized the first world championship, which evolved into what is now Formula 1. They make the rules governing the construction of the cars, and they enforce the racing rules when cars are on-track. Typically major decisions are handled by the FIA president, who since 1991 has been Max Mosley. Pay attention, because you'll see his name pop up a lot in F1-land. Before Max, the president was Jean-Marie Balestre (facing the camera at right), who enters into play next. Ayrton Senna. For F1 die-hards, that name recollects one of the best drivers in recent history, perhaps the best of all time. Senna had an amazing career in F1 including 65 poles, 80 podiums, and 41 wins in 162 races (basically 10 years). Senna's time in F1 was tragically cut short in an accident at Imola (Italy) in 1994 in which he was killed. We'll talk more about this amazing driver in the future, but for now I'm going to focus on one of the biggest drama's in F1 history.

Ayrton Senna. For F1 die-hards, that name recollects one of the best drivers in recent history, perhaps the best of all time. Senna had an amazing career in F1 including 65 poles, 80 podiums, and 41 wins in 162 races (basically 10 years). Senna's time in F1 was tragically cut short in an accident at Imola (Italy) in 1994 in which he was killed. We'll talk more about this amazing driver in the future, but for now I'm going to focus on one of the biggest drama's in F1 history.In 1988, McLaren enlisted two amazing drivers; Alain Prost (already a double world champ) and relative F1-newcomer Ayrton Senna. That year between the two of them they won 15 of 16 races, with Senna winning his first championship. As you might imagine, there was a rivalry brewing between the two drivers and the following year it became even more intense.

Going into the second-last race of the 1989 season, Prost was in the points lead, and Senna needed to win the race if he was to stay in contention for the championship. The two McLaren's qualified in the front row, and before the race Prost said something to the effect that he would not yield to Senna just to avoid the embarrassment of the two McLaren's taking each other out. And that's exactly what happened…

Going into the second-last race of the 1989 season, Prost was in the points lead, and Senna needed to win the race if he was to stay in contention for the championship. The two McLaren's qualified in the front row, and before the race Prost said something to the effect that he would not yield to Senna just to avoid the embarrassment of the two McLaren's taking each other out. And that's exactly what happened… Senna tried to pass Prost on the inside going into Susuka's chicane. Prost turned into Senna, their wheels tangled, and both cars went off-track onto the chicane escape road. Prost got out of his car, thinking that he had won the championship with Senna out of contention. However, Senna's car was in a dangerous position on-track, and as the corner-workers pushed his car, he was able to bump-start the engine. He got back on track and went to the pits for repairs, and then rejoined the race.

Senna tried to pass Prost on the inside going into Susuka's chicane. Prost turned into Senna, their wheels tangled, and both cars went off-track onto the chicane escape road. Prost got out of his car, thinking that he had won the championship with Senna out of contention. However, Senna's car was in a dangerous position on-track, and as the corner-workers pushed his car, he was able to bump-start the engine. He got back on track and went to the pits for repairs, and then rejoined the race.And won.

However, the FIA (then president Jean-Marie Balestre) decided that Senna did not take the chicane (obviously because of the accident) and that the push-start was illegal, and not only disqualified him from the race, but also gave him a heavy fine and actually suspended his Super Licence (which one needs to race in F1).

Now the real drama starts. Prost went to Ferrari for 1990 while Senna stayed with McLaren. Ironically, the pair came into the second-last race, again the Japanese Grand Prix at Suzuka, with Senna leading Prost by 9 points. Senna was able to take pole, however the pole position at Suzuka was on the right side of the track, off the racing line. This area of the track was dirty and disadvantageous for the start, and before qualifying Senna asked the marshals to move the pole position to the left side of the track, which they agreed to do, but Jean-Marie Balestre later overruled.

Now the real drama starts. Prost went to Ferrari for 1990 while Senna stayed with McLaren. Ironically, the pair came into the second-last race, again the Japanese Grand Prix at Suzuka, with Senna leading Prost by 9 points. Senna was able to take pole, however the pole position at Suzuka was on the right side of the track, off the racing line. This area of the track was dirty and disadvantageous for the start, and before qualifying Senna asked the marshals to move the pole position to the left side of the track, which they agreed to do, but Jean-Marie Balestre later overruled.Senna was infuriated by what he saw as the FIA conspiring against him, and stated before the race that he would enter the first corner without regards for Prost's car. Prost got the better start his position in 2nd on the left side of the track, and true to Senna's word, he collided with Prost and both cars were out of the race, this time making Senna the champion!

A year later Senna reflected on the situation. "So I said to myself, 'OK, whatever happens, I'm going to get into the first corner first — I'm not prepared to let the guy (Alain Prost) turn into that corner before me. If I'm near enough to him, he can't turn in front of me — he just has to let me through.' I didn't care if we crashed; I went for it. And he took a chance, turned in, and we crashed."

A year later Senna reflected on the situation. "So I said to myself, 'OK, whatever happens, I'm going to get into the first corner first — I'm not prepared to let the guy (Alain Prost) turn into that corner before me. If I'm near enough to him, he can't turn in front of me — he just has to let me through.' I didn't care if we crashed; I went for it. And he took a chance, turned in, and we crashed."This wasn't the first or last time that drivers would be accused, justified or not, of deliberate accidents and other 'unsporting' conduct, such as blocking. One of the more recent incidents involved one Michael Schumacher at F1's most famous venue, Monaco. Schumacher entered the race behind rival Fernando Alonso of Renault. As 2006 was likely to be Schumacher's last season, he was especially motivated to win at Monaco as it would tie Senna's record for most wins at Monaco (six).

During qualifying, Schumacher had set the fastest lap and was on pole. However, on Schumacher's last lap before qualifying ended, he was ahead of Alonso on the track, and running a pace off of his best time. Alonso, also on his last lap, was running at a pace that would put him on pole. Its suspected that Schumacher knew this, and entering one of the final corners, a tight 180 degree turn, spun his car 90 degrees, effectively blocking the track and forcing a caution flag, and ruining Alonso's very fast last lap.

During qualifying, Schumacher had set the fastest lap and was on pole. However, on Schumacher's last lap before qualifying ended, he was ahead of Alonso on the track, and running a pace off of his best time. Alonso, also on his last lap, was running at a pace that would put him on pole. Its suspected that Schumacher knew this, and entering one of the final corners, a tight 180 degree turn, spun his car 90 degrees, effectively blocking the track and forcing a caution flag, and ruining Alonso's very fast last lap.After this there was enormous controversy as to if Schumacher deliberately spun his car, or if it was an honest accident. Some claimed that a driver of his skill would not be likely to make such a mistake at a slow part of the track, on a lap he knew was already slower than his best. Others are adamant that it was an honest and human mistake.

The FIA took issue with Schumacher's actions finding them to "seem deliberate", and moved him to the back of the grid, taking his pole, and promoting Alonso from 2nd to 1st. Ferrari principal Jean Todt said he was disgusted by the decision, but Schumacher was not alone. Renault driver Giancarlo Fisichella ("john-carlo fizzi-kella") was penalized his three fastest laps in qualifying for blocking David Coulthard. Still, Schumacher showed his stuff by starting 22nd and finishing 5th on a track where passing is notoriously difficult. This wasn't Schumacher's first brush with controversy; he was accused of deliberate wrecks in 94 and 97. But he'll still be remembered as one of the modern greats, having won 7 championships, 76 fastest laps, and 68 poles.

Hopefully what I've shown is the drama and controversy that's a part of F1, and the extremes people are willing to go to in order to win. The pressure placed on drivers and teams to win and win consistently is enormous, and the drivers' own personal ambitions and overwhelming desire for victory can be all-consuming. Such is the passion that surrounds F1.

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Qualifying

Starting up front is a huge advantage in F1 because overtaking (passing) is difficult. The leading car tends to leave so-called 'dirty' air in its wake, which does two things. One, it creates less drag on the car following, allowing the trailing car to accelerate faster. This is called drafting or slip-streaming. Two, the wake also reduces the effectiveness of the trailing car's wings, leading to less grip which slows the trailing car down in the corners.

Starting up front is a huge advantage in F1 because overtaking (passing) is difficult. The leading car tends to leave so-called 'dirty' air in its wake, which does two things. One, it creates less drag on the car following, allowing the trailing car to accelerate faster. This is called drafting or slip-streaming. Two, the wake also reduces the effectiveness of the trailing car's wings, leading to less grip which slows the trailing car down in the corners.

Therefore the current overtaking strategy is to try to get a draft on the straights, but then fall back enough in the corners to maintain downforce. The passing move itself almost always comes under braking. The trailing driver will try to brake later than the lead driver, get ahead, and stay ahead out of the corner. Sometimes the trailing driver ends up braking too late and either going too far into the corner, or going off-track. Either means the trailing driver's pass won't stick and he'll have to do it all over again.

Qualifying is done in three 15-minute periods in a format known as 'knock-out'. During each period, cars are free to run on the track, trying to set their best single-lap time. Cars can run as many laps as they want, pit, and change tires. If a car has started a lap when the session ends, the car is allowed to finish its current lap. In the first period, the slowest 6 cars are assigned grid spots 17 to 22 and are excluded from the next two sessions. In session two, again the slowest 6 cars are assigned spots 11 to 16 and excluded from the next session.

In the third and final session, the top 10 cars must declare how much fuel they want to start the race with. After the third session, these cars are allowed to refill their cars to account for the fuel used during the qualifying session. This is where race strategy begins to enter into play. An F1 car can carry around 26 gallons of fuel, which weights about 162 lbs, although the cars are rarely filled to capacity. Each lap on-track burns between 4.8 and 6.5 lbs of fuel. Any reduction in weight results in better laptimes, so the amount of fuel on-board is critical. During sessions 1 and 2 the cars run as little fuel as possible. However, since cars in the final session must start with their race fuel load, they start lapping immediately, trying to burn off as much fuel as possible before trying to post a fast lap.

Once qualifying starts, several rules go into effect, putting the cars in a condition known as parc ferme ('park firm-ay') which is a special area of the paddock were the cars are put after qualifying and the race to ensure they are not touched by the teams. Parc ferme also specifies a set of allowable adjustments to the car. During this, the teams can adjust the front wing angle to put more or less front down-force on the car. They can also attach small blowers to cool the brakes and engine. However little else can be changed on the car once qualifying starts. This is to prevent the teams from building special qualifying parts and then changing them before the race.

Once qualifying starts, several rules go into effect, putting the cars in a condition known as parc ferme ('park firm-ay') which is a special area of the paddock were the cars are put after qualifying and the race to ensure they are not touched by the teams. Parc ferme also specifies a set of allowable adjustments to the car. During this, the teams can adjust the front wing angle to put more or less front down-force on the car. They can also attach small blowers to cool the brakes and engine. However little else can be changed on the car once qualifying starts. This is to prevent the teams from building special qualifying parts and then changing them before the race.

Top position in qualifying is called Pole Position (as in pretty much every form of motorsports), and history judges drivers not only on how many wins they scored, but also how many poles they captured and how many fast laps they set. Its considered a 'trifecta' when a driver does all three in one race; a display of total dominance over the rest of the field.

Friday, July 6, 2007

Aero

Thus the idea of using an inverted wing was conceived, using the air to push the car down onto the track. Not only does this counteract lift, but it creates downforce which increases the traction of the tires. A modern F1 car generates so much downforce that it could drive upside down at only 60mph!

The first car to sport an inverted wing was Jim Hall's Chapparal 2E (at right) racing in Can-Am series. In F1 a year later, Colin Chapman of Lotus introduced the 49b which had small front winglets and a flat tail. One race later the car had a huge wing on the back; the Lotus took pole by nearly 4 seconds!

The first car to sport an inverted wing was Jim Hall's Chapparal 2E (at right) racing in Can-Am series. In F1 a year later, Colin Chapman of Lotus introduced the 49b which had small front winglets and a flat tail. One race later the car had a huge wing on the back; the Lotus took pole by nearly 4 seconds!The Lotus before and after aero development:

F1 cars generate downforce in numerous ways. The most important are the front and rear wings. The rules limit how wide these can be, and only the front wing can be adjusted during the race. Wings cannot be designed to move. Most teams will develop specific front and rear wings for every track during the year to meet the downforce requirements of that track. Increasing downforce increases drag, which decreases top speed. Teams try to find the right balance of top speed and downforce to give the best lap time for a given circuit.

The cars also generate downforce through ground effects. By running the car as low as possible, the air beneath the car creates a low-pressure area that effectively sucks the car down towards the track. The rear of the car features guides called 'diffusers' that accelerate the air under the car out the back, preserving the low pressure under the car.

There is not a minimum ride height, however all of the cars have a 'skid plank' underneath that runs the length of the car. You can see the plank on Robert Kubica's airborne car. If this plank wears more than 1mm by the end of the race, the car is disqualified. This means that the teams must adjust their suspension to avoid bottoming out under heavy downforce.

There is not a minimum ride height, however all of the cars have a 'skid plank' underneath that runs the length of the car. You can see the plank on Robert Kubica's airborne car. If this plank wears more than 1mm by the end of the race, the car is disqualified. This means that the teams must adjust their suspension to avoid bottoming out under heavy downforce.The effect of aerodynamics influences the design of almost every part of the car. Current cars feature high noses, which allows the front wing to run the entire width of the car, and avoids upsetting air that will pass underneath the car. The designs of the transmission, suspension, exhaust, and radiators are all made with aero packaging as a top priority. The suspension members are tear-dropped shaped in profile to better cut through the air.

The cars are also sensitive to lateral air movement. A change in wind direction can affect how the car performs on the track. Also, the car is almost always changing direction, meaning the air is flowing at an angle over the surfaces. Teams work very hard to design aero elements that can utilize this airflow to make good downforce.

Aerodynamics tends to be very complicated and hard to model, which leads to lots of wind tunnel testing. All of the top teams have their own wind tunnels, and generally run them 24/7 during the season. Every tweak to an aero surface requires re-evaluation of the entire aero package. Its not unusual for every bodywork component of the car to change three or four times during the season. Unfortunately, this also means that smaller budget teams lack the resources to compete in aero development.

Electronic aids

Traction control (TC) uses electronics to prevent wheelspin. With 750 hp on tap, F1 cars can easily spin their rear wheels into big smoky clouds. You can see one of the Renaults in the second spot on grid doing exactly that. However, burning rubber isn't the fastest way down the track. To prevent this, there are magnetic sensors on each wheel hub. These sensors detect how fast each wheel on the car is spinning. If one of the rear wheels begins to spin faster than the other wheels, the electronics will cut spark to one or more cylinders of the engine, briefly reducing power and allowing the tires to regain traction. From a driver's perspective, it is not as important to smoothly apply throttle coming out of turns; they can floor it and let the TC work for them. The amount of TC can be controlled by the driver from the steering wheel. The TC can also be disabled via a steering wheel button to allow the driver to spin the car, which is necessary if the car has spun and is facing backwards on the track.

Traction control (TC) uses electronics to prevent wheelspin. With 750 hp on tap, F1 cars can easily spin their rear wheels into big smoky clouds. You can see one of the Renaults in the second spot on grid doing exactly that. However, burning rubber isn't the fastest way down the track. To prevent this, there are magnetic sensors on each wheel hub. These sensors detect how fast each wheel on the car is spinning. If one of the rear wheels begins to spin faster than the other wheels, the electronics will cut spark to one or more cylinders of the engine, briefly reducing power and allowing the tires to regain traction. From a driver's perspective, it is not as important to smoothly apply throttle coming out of turns; they can floor it and let the TC work for them. The amount of TC can be controlled by the driver from the steering wheel. The TC can also be disabled via a steering wheel button to allow the driver to spin the car, which is necessary if the car has spun and is facing backwards on the track.Launch control. The start of an F1 race is always a standing start, meaning the cars start from a standstill. Launch control works similar to TC in that it determines the optimal amount of slip for the best start and modulates the power to achieve that.

Rear differential. In an F1 car the rear differential is hydraulically controlled and adjustable by the driver. A rear differential serves several purposes. First, it takes a single spinning input (the driveshaft from the transmission) and converts it into two spinning outputs (the half-shafts) that feed to each rear wheel. The differential also allows the two rear wheels to turn at different speeds relative to each other. This is necessary since the outside wheel in a corner must turn faster than the inside wheel. Finally, the differential also limits the amount of speed difference between the two wheels under both acceleration and deceleration. This limit or locking-effect is called 'limited-slip'. On American muscle cars it was often called Posi-traction.

Rear differential. In an F1 car the rear differential is hydraulically controlled and adjustable by the driver. A rear differential serves several purposes. First, it takes a single spinning input (the driveshaft from the transmission) and converts it into two spinning outputs (the half-shafts) that feed to each rear wheel. The differential also allows the two rear wheels to turn at different speeds relative to each other. This is necessary since the outside wheel in a corner must turn faster than the inside wheel. Finally, the differential also limits the amount of speed difference between the two wheels under both acceleration and deceleration. This limit or locking-effect is called 'limited-slip'. On American muscle cars it was often called Posi-traction. The F1 driver can adjust the amount of locking via a knob on the steering wheel which varies the hydraulics in the differential. Some drivers will adjust this from corner to corner. However, the differential cannot be automatically controlled; it must be adjusted only by the driver.

The F1 driver can adjust the amount of locking via a knob on the steering wheel which varies the hydraulics in the differential. Some drivers will adjust this from corner to corner. However, the differential cannot be automatically controlled; it must be adjusted only by the driver. Antilock braking (ABS) is banned in F1. When braking, the tires can 'lock up' when excessive pressure is applied. The brakes squeeze the brake rotor so hard that the wheel literally stops rotating. This appears as a stopped wheel and a puff of smoke as the stopped and sliding tire burns. As mentioned above, tires do not work their best when they are smoking!

Antilock braking (ABS) is banned in F1. When braking, the tires can 'lock up' when excessive pressure is applied. The brakes squeeze the brake rotor so hard that the wheel literally stops rotating. This appears as a stopped wheel and a puff of smoke as the stopped and sliding tire burns. As mentioned above, tires do not work their best when they are smoking! An ABS system works very similar to the TC system, and in fact uses the exact same magnetic sensors to detect when a wheel is stopped. When this happens, the ABS computer instructs a valve in the braking system to open for a fraction of a second, releasing the brake pressure on the locked wheel. This release of brake force allows the tire to resume rolling and regain traction. If you've ever panic-braked in a modern car and felt the brake pedal pulse, you engaged the ABS. Those pulses are the rapid opening and closing of the brake valves.

An ABS system works very similar to the TC system, and in fact uses the exact same magnetic sensors to detect when a wheel is stopped. When this happens, the ABS computer instructs a valve in the braking system to open for a fraction of a second, releasing the brake pressure on the locked wheel. This release of brake force allows the tire to resume rolling and regain traction. If you've ever panic-braked in a modern car and felt the brake pedal pulse, you engaged the ABS. Those pulses are the rapid opening and closing of the brake valves.Contrary to some people's belief, any good modern ABS system will out-perform any non-ABS system, no matter who the driver. This is not only because the computer can react faster, but also because it can control all four wheels independently. However, since ABS is banned, its up to the driver's own reflexes to push the brakes to just below the point of lock-up, and rapidly modulate pressure when a wheel locks up. Some drivers can even emulate a form of ABS by modulating the brake pressure up to five times a second. The drivers can adjust the brake pressure bias from front to rear via a bias bar in the cockpit. This allows them to put more brake pressure up front for more aggressive braking, or adjust bias to compensate for tire wear during the race. However, the bias cannot be adjusted left to right, which could be used for faster turn-in entering corners.

The Transmission

The transmission's job is to take the output of the engine, turning at 16-19k rpm and turn it into an output that matches the speed of the car's wheels. Most of the F1 cars today use seven forward gears. The engineers will designate each gear's ratio for each track during the season to make maximum use of the engine. Gear ratios are often changed several times during practice depending on things like wind and driver preference.

The transmission's job is to take the output of the engine, turning at 16-19k rpm and turn it into an output that matches the speed of the car's wheels. Most of the F1 cars today use seven forward gears. The engineers will designate each gear's ratio for each track during the season to make maximum use of the engine. Gear ratios are often changed several times during practice depending on things like wind and driver preference.In an F1 car, shifting is done by two paddles on the back of the steering wheel. Typically pulling the right paddle shifts up and the left paddle shifts down. The gears are selected sequentially, meaning the driver cannot skip gears, although they can pull the paddles rapidly to cycle through the gears. The clutch is only used to start the car from a stop. The electronics handle matching engine rpms and cutting power during the actual shift. The driver keeps his foot flat on the throttle. An up-shift takes less than 0.2 seconds. The clutch is also a paddle on the steering wheel since the left foot is used for braking, and there is not much room in the foot-well.

In 2007 several teams started using so-called 'seamless shift' gearboxes. Normally on an up-shift the current gear is disengaged, the throttle is cut, the electronics wait for the engine revs to drop to the appropriate rpm, and then the next gear is engaged. In the seamless shift units, the waiting period for the revs to drop is no longer necessary. The seamless units use ratchets to allow the engine to engage the next higher gear without needing to be synchronized in speed. This reduces up-shift times to less than 0.1 seconds. Its also very hard on the transmission and the hydraulics that operate it, and 2007 has seen numerous gearbox failures.

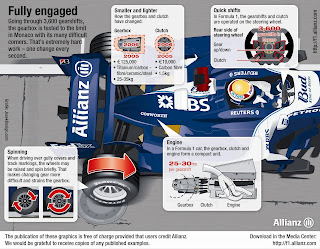

In 2007 several teams started using so-called 'seamless shift' gearboxes. Normally on an up-shift the current gear is disengaged, the throttle is cut, the electronics wait for the engine revs to drop to the appropriate rpm, and then the next gear is engaged. In the seamless shift units, the waiting period for the revs to drop is no longer necessary. The seamless units use ratchets to allow the engine to engage the next higher gear without needing to be synchronized in speed. This reduces up-shift times to less than 0.1 seconds. Its also very hard on the transmission and the hydraulics that operate it, and 2007 has seen numerous gearbox failures.As with the monocoque, Allianz has published an excellent technical graphic on F1 gearboxes.

F1 Engines

The valves of an engine are held closed by valve springs. When the cam turns, its lobe pushes the valve down against the spring and as the lobe passes the valve, the spring pushes the valve back up to close it. This works well until you reach very high redlines at which point something called 'hysteresis' happens to the valve spring. Basically the spring can't push the valve closed fast enough and the valve 'floats', unable to completely close before its opened by the cam again. This is bad.

So some engineers at Renault's F1 team came up with a solution: use pneumatics in place of valve springs. Pneumatics use air to move things and therefore do not suffer from hysteresis. Pressurized nitrogen is used in the F1 engines to push the valves back up. This allows for reliable valve operation well past 21k rpms. MotoGP motorcycles are the only other form of racing to use pneumatic valves.

So some engineers at Renault's F1 team came up with a solution: use pneumatics in place of valve springs. Pneumatics use air to move things and therefore do not suffer from hysteresis. Pressurized nitrogen is used in the F1 engines to push the valves back up. This allows for reliable valve operation well past 21k rpms. MotoGP motorcycles are the only other form of racing to use pneumatic valves.In F1, you must qualify and race the same engine in two consecutive races. This rule was designed to control costs so that the teams did not build 'grenade' engines that would only last 1 qualifying session or one race. In practice, teams are free to run of their engines and change at any time. If your designated race engine blows up in its first qualifying or first race, you must take a 10-spot grid penalty for the next race.

The engine is also a structural (or 'stressed') member of the car. This means that the engine literally holds the rear of the car to the monocoque! The front of the engine is bolted to the rear bulkhead of the monocoque, and the rear of the engine is bolted to the transmission. The rear suspension is mounted to the transmission (also a stressed member). Lotus was one of the first teams to embrace this concept, as you can see here on their 1967 car.

The engine is also a structural (or 'stressed') member of the car. This means that the engine literally holds the rear of the car to the monocoque! The front of the engine is bolted to the rear bulkhead of the monocoque, and the rear of the engine is bolted to the transmission. The rear suspension is mounted to the transmission (also a stressed member). Lotus was one of the first teams to embrace this concept, as you can see here on their 1967 car. Using the engine and transmission as stressed members allows the monocoque to be shorter and eliminates extra weight. This is in stark contrast to a NASCAR car in which the engine and transmission are mounted within a tube frame, and the suspension members and bodywork are bolted to this frame.

Using the engine and transmission as stressed members allows the monocoque to be shorter and eliminates extra weight. This is in stark contrast to a NASCAR car in which the engine and transmission are mounted within a tube frame, and the suspension members and bodywork are bolted to this frame.

Engines: output

Displacement. Displacement is total volume inside the cylinders of an engine if every piston was at its bottom-most position. So if you have a 4 cylinder engine and each cylinder is 500 cubic centimeters (cc's) the total displacement is 2 liters (500 * 4 = 2000 cc's). The more the displacement, the more air and fuel can be taken into the engine, resulting in more power. Displacement is in general an excellent measure of how much power an engine can make.

Torque. Torque is a measure of force. Its an instantaneous measurement, meaning it doesn't take into account time. You can think of torque like trying to turn a wrench; the torque is the force you are applying to the handle. We express torque in terms of force over a distance; typically the force of 1 pound over 1 foot, aka ft-lb (foot-pounds). The amount of torque an engine makes varies based on how fast the engine is turning.

RPM's. Revolutions per minute. This is how many times the crankshaft of the engine turns in one minute.

Horsepower. Horsepower is how we measure the power of an engine. Hp = torque*revolutions-per-minute / 5252. The '5252' is a constant, and it also means that at 5252 rpm's, torque and hp will always be equal. Since the amount of hp is based on how fast the engine is turning, hp will almost always increase as rpm's increase. In terms of how fast our car can accelerate, hp is the most useful figure.

RWHP or BHP. Rear-wheel horsepower or brake horsepower. This refers to horsepower that was actually measured at the wheels of a car using a device called a dynamometer, (or dyno for short). This tells us how much power is actually getting to the ground. This is less than the horsepower at the crankshaft of the engine since there are frictional losses in the transmission and differential.

Redline. The maximum rpm it is safe to spin the engine at. For a production car, this is typically 6-7k rpms. For an F1 car, it is capped at 19k rpms.

F1 teams aren't too keen to publish their dyno charts, so at right are a couple sample dyno plots from a production car engines. The chart has two lines, representing torque and horsepower. Sometimes it can be hard to know which line is which, so a tip is that peak horsepower nearly always occurs at a higher rpm (farther to the right) than peak torque.

F1 teams aren't too keen to publish their dyno charts, so at right are a couple sample dyno plots from a production car engines. The chart has two lines, representing torque and horsepower. Sometimes it can be hard to know which line is which, so a tip is that peak horsepower nearly always occurs at a higher rpm (farther to the right) than peak torque. Looking at the power curve can tell you a lot about the characteristics of the engine. In the top dyno plot, the torque smoothly increases and retains a nice flat curve in the meat of the powerband. A flat plateau in the torque curve, and a nice linear diagonal line for horsepower means that the engine will respond proportionally to throttle input. In the second graph, a turbocharged engine from the MkIV Toyota Supra shows an engine with a 'peaky' powerband. Because of the character of the turbo, this engine doesn't make nearly as much power at low rpms as it does at high rpms. The torque curve jumps abruptly as the turbo spools up. We'll discuss turbos more later.

Looking at the power curve can tell you a lot about the characteristics of the engine. In the top dyno plot, the torque smoothly increases and retains a nice flat curve in the meat of the powerband. A flat plateau in the torque curve, and a nice linear diagonal line for horsepower means that the engine will respond proportionally to throttle input. In the second graph, a turbocharged engine from the MkIV Toyota Supra shows an engine with a 'peaky' powerband. Because of the character of the turbo, this engine doesn't make nearly as much power at low rpms as it does at high rpms. The torque curve jumps abruptly as the turbo spools up. We'll discuss turbos more later. Anyway, because the engine is making its best power in a narrow range, it would benefit from a gearbox with closely spaced gears, shifting more frequently to keep the rpm's up. In that respect, this engine is similar to an F1 engine. Both like to be rev'ed high and kept high to make the best power.

Engines: the basics

Suck (intake): The engine works by taking in air, mixing fuel into the air, and then burning this mixture. The first step is to get the mixture into the cylinder. A cam pushes the intake valves open while at the same time the piston is moving down in the cylinder. This sucks air into the cylinder. Fuel injectors spray a fine mist of fuel into the air that is being sucked in.

Squish (compression): The intake valves close, trapping the mixture in the cylinder. The piston now moves up, compressing the mixture.

Bang (ignition): At the top of the cylinder is the spark plug. The plug has two metal electrodes that are separated by a tiny gap. When electricity is applied to both of these electrodes, it jumps across the gap, creating a spark. This spark ignites the fuel-air mixture, which then burns, creating heat and pressure, and pushing the piston down. This is where the engine is actually doing work and creating power.

Blow (exhaust): Once the cylinder has been pushed all the way down, the mixture is completely burned and what remains are by-products of the combustion. The cam now opens the exhaust valves and the piston moves back up, pushing the spent gases out of the cylinder. Then the cycle starts all over again.

To make more sense of this, take a look at the animation on this page.